Jon Irabagon, Metamodernism, and a Contemporary Compositional Technique:

My English teachers would be proud of me for this one. I’ve finally taken their advice: I started with a topic that was way too big, and decided to narrow it down to something I can actually tackle with an appropriate amount of depth.

The original piece was going to be about how the emerging philosophical movement called metamodernism can breathe new life into the world of straight ahead jazz. But invariably during my attempts at writing it, I found myself needing to tackle multi-book length questions just to lay the groundwork for the conversation. Questions like “what are modernism, postmodernism, and metamodernism? How do these philosophies apply to academic or cultural movements outside of music? What problems does each movement solve and create respectively?” I found myself skimming topics that deserved way more, so I’m cutting this paper down.

This post will be about an awesome and hilarious compositional technique, and about the way that technique manifests itself in the work of some of my favorite contemporary artists. The technique sits squarely beneath the larger philosophical umbrella of metamodernism, but instead of trying to write about why the technique is metamodernist, for now I’ll just declare that employing this technique brings you closer to the heart of a metamodernist philosophy. If you don’t want to take my word for this I’ve also tacked on an earlier (failed) draft to the end of this post where I try to get into the weeds of the other -isms.

The technique operates as follows: start with a ridiculous or ironic premise and then add labor and sincerity until the artistic product becomes completely serious.

This technique didn’t have a name, so I decided to name it myself. I googled the Latin translations for ridiculousness, becoming, and seriousness, and then smashed those words up together to create this term. I tried a bunch of options: Ridiculum-facio-gravis? Ridiculum-gravis? Ridiculum-fit-gravitas? Eventually I settled on Gravitas Ridiculum. It’s probably grammatically incorrect Latin, but I think it rolls off the tongue and I need a term to describe what I’m about to talk about.

My first exposure to someone employing Gravitas Ridiculum was appropriately bizarre. It was this video:

The video sits in a liminal space: yes it’s hilarious, silly, ironic, and a full on meme, but if you look past the bizarre facade for a second it becomes apparent that he’s taking the acting and the message incredibly seriously, and the intensity makes it kind of avant-garde. Mashing up an intentionally corny script and weird production value with a really intense approach gives the video a legitimately unique feeling. And interestingly, when I watch this video, I find myself both laughing at the absurdity and legitimately motivated. I’m not the only one. Here are some of the top comments on the video:

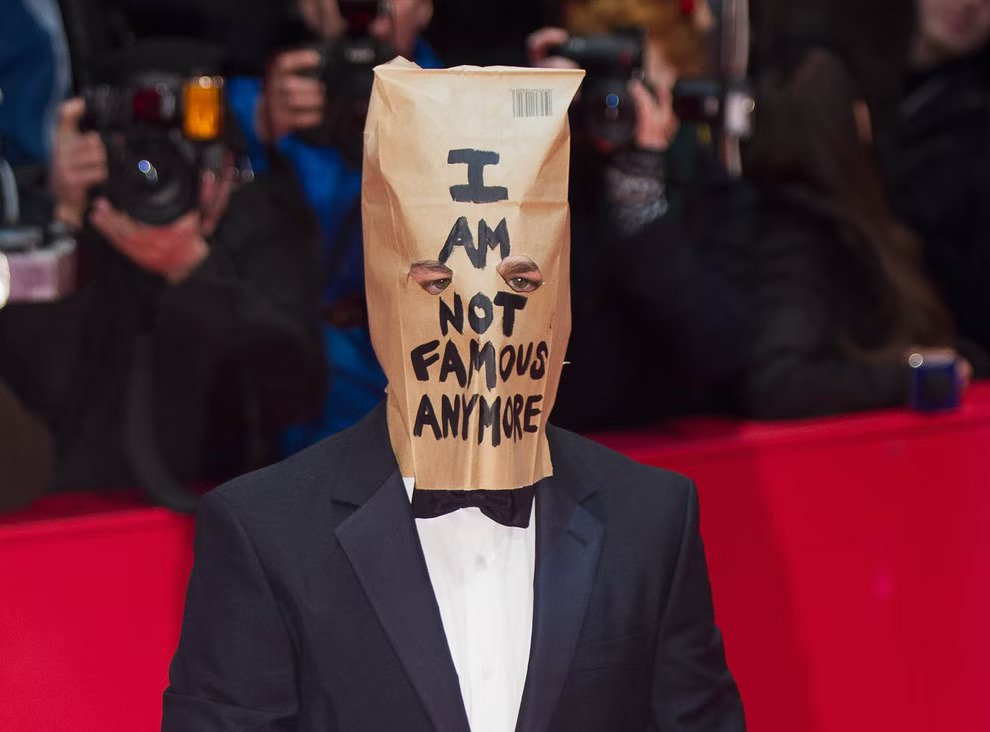

The video sent me down a Shia LaBeouf YouTube rabbit hole. He seemed pretty unhinged around the time it came out, and was engaging with a bunch of whacky publicity-stunt-meets-performance-art type projects. For one project he walked the red carpet at a film festival while wearing a giant paper bag over his head with the words “I am not famous anymore” written across the front.

In another, he filmed himself watching and reacting to all of his own movies back to back, titling the project #ALLMYMOVIES. In yet another he met people one-on-one in an LA art gallery for 10 minutes at a time to bawl his eyes out in front of them.

Perhaps the project that most clearly exemplifies Gravitas Ridiculum could be his performance art piece entitled Meditation for Narcissists. In it, LaBeouf jumps rope while staring at “his digital reflection,” (a live webcam showing himself) for an entire hour. Later, the video is played at art galleries, and viewers are invited to jump rope while staring at Shia.

The project starts with a pseudo-edgy premise, some flashy self-aware/ironic detachment, and is made stranger by Shia’s celebrity. At first glance it has all the hallmarks of a postmodernist piece. Postmodernists are the ones who say “We’re questioning your concept of what art even is.” And the starting point of Meditation for Narcissists seems like a bread and butter postmodernist critical commentary. The artists seemingly posture themselves around questions like “what is art, anyways? Could jumping rope in an art museum be art? Is it more or less artistically valid if the piece is being performed by that guy from Even Stevens?” Postmodernism is questions like these; it’s Marcel Duchamp putting a urinal in the Museum of Modern Art.

But the departure from postmodernism in Meditation for Narcissists is this: if you actually participate in the piece and jump rope with Shia as the artists intend, you cannot maintain the irony. This is the point. There’s no way to ironically jump rope for an entire hour. Your heart rate will rise, you’ll break a sweat, and, importantly, the experience will become legitimately meditative. This is Gravitas Ridiculum: It’s taking a project that’s conceptual in its form and groundwork, and extremely not conceptual in its execution. It’s adding labor to conceptual art until you can’t really say that it’s conceptual anymore.

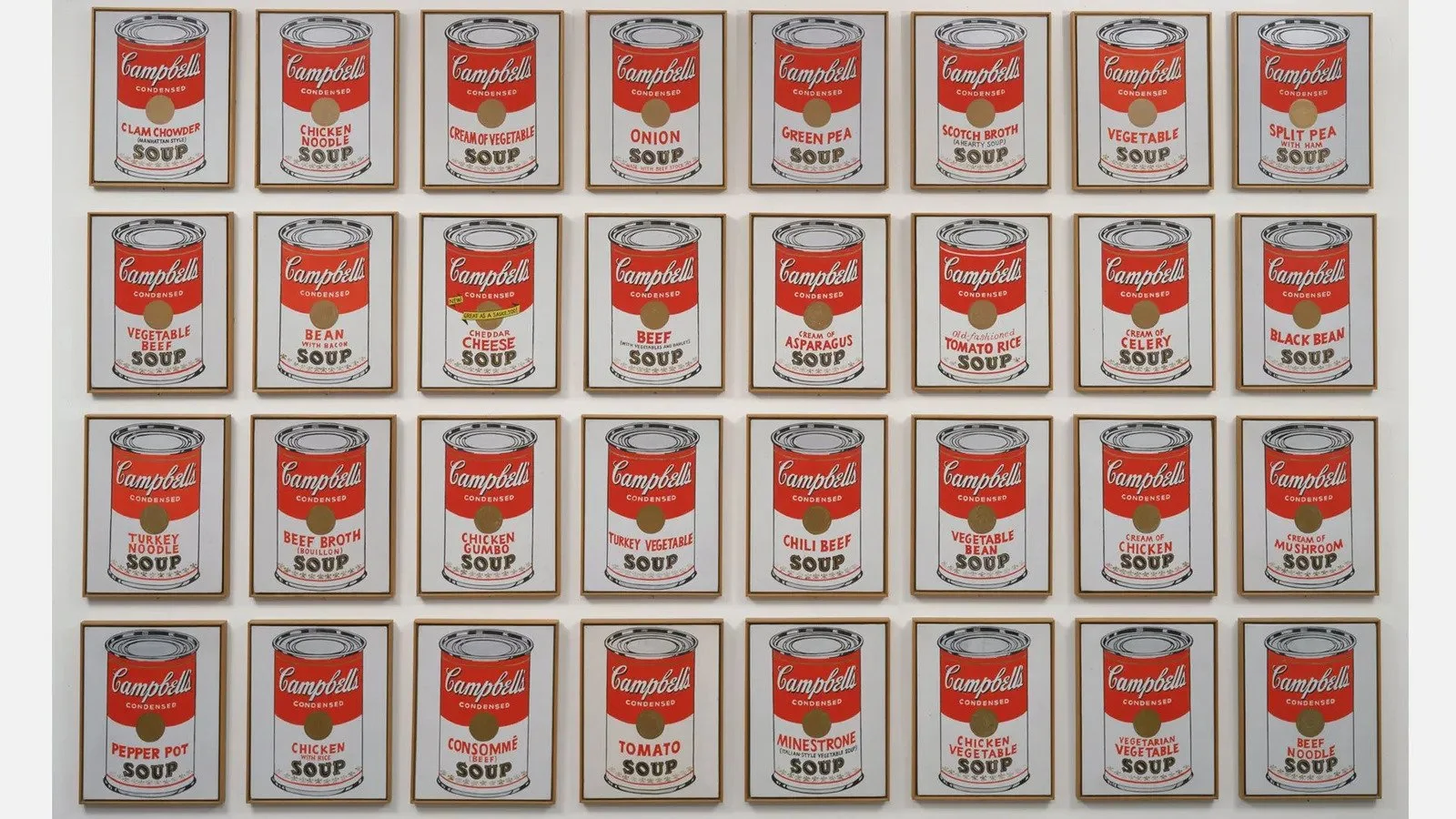

Sculptor Tom Sachs exhibits Gravitas Ridiculum to an extreme degree in many of his pieces. His works often begin with references to his highly consumerist culture/upbringing in the 70’s and intensely brand oriented imagery. His pieces utilize crappy materials like plywood, styrofoam, hot glue, and a variety of items you would probably associate more closely with a construction site than with an art museum. But what separates his work from postmodernists like Andy Warhol (who also used brand imagery) or Jeff Koons/Damien Hirst (who also questioned which materials could be valid in the context of “high art”) is the unbelievable amount of labor he puts into his work. (It’s not to say the other artists didn’t work hard, it’s just that Tom’s work is about the labor to a large degree).

Andy Warhol: Campbell’s Soup Cans

Jeff Koons: Three Ball Total Equilibrium Tank

Tom Sachs: Chanel Breakfast Nook and Guillotine

Gravitas Ridiculum runs deep in Tom’s veins. When speaking on his own work, he’s said:

“By building to an extreme degree of detail and depth, the experience becomes real. I have a space program, and it is real. What I can’t do with kerosene and titanium, I do with hot glue and cardboard and plywood. True authenticity also demands endurance. Do it for a long time, whatever it is. Two years is just an interest, do something for five years it’s a hobby. Do something for twenty years and you begin to build a sense of mastery, and the holes in your position on the thing are too small to be of any meaningful consequence… Art is a creative act, and too much creativity can ruin it. It’s a discipline.”

The art in Tom’s work comes from the labor itself.

To my knowledge, only one artist in jazz employs Gravitas Ridiculum to the extent necessary to squarely classify them as a “metamodernist artist,” and that person is Jon Irabagon.

His album Blue has probably sparked more outrage than any jazz album since the turn of the millennium. The album, a note-for-note recreation of the entirety of Miles Davis’ Kind of Blue, was recorded by Mostly Other People Do the Killing (a jazz collective which includes Irabagon) in 2014. It infuriated people from every part of the traditionalist-vs-modernist jazz spectrum, but it also has ardent defenders. Yet, it seems the conversation surrounding the album is lacking adequate appreciation of one specific detail: it is an enormous task to transcribe an album note for note and then perform it back as a band in real time.

This is the labor aspect that makes this album exhibit Gravitas Ridiculum. The premise is conceptual: They’re questioning the nature of “what is jazz? Is jazz becoming a classical art form? Is this album jazz if we don’t actually improvise?” (and the questions don’t stop here). But the conceptual groundwork finds a new life in the insanely tedious labor aspect. You have to sit down and transcribe every single ride cymbal skip beat in Jimmy Cobb’s right hand. You have to transcribe every note in the piano left hand. The work becomes as much a part of the art as the conceptual questioning. And it’s legitimately new; to my knowledge there is no other project like it.

You can tell a piece of art exemplifies Gravitas Ridiculum when you ask two consecutive questions: 1: Are they serious? And 2: How could anyone doing all that work not be serious? Many of Jon’s albums exemplify at least a little bit of this flavor; taking a funny or crazy “what if we ______” idea and seriously committing to seeing it through, finding both the artistic merits of the idea and uncharted creative territory along the way. A perfect example of this is his album, Foxy.

The premise is: “What if we recorded an entire album where we just play the changes to the Sonny Rollins tune Doxy?” It’s a conceptual question about the meaning of form and the ideas about theme+variations that often go unchallenged in jazz (in fact, Irabagon writes some heavy conceptual commentary in the album’s liner notes regarding these topics). But the conceptual quickly fades to the experiential through wholehearted commitment to the concept. The album is 78 minutes of saxophone trio (featuring master drummer Barry Altschul sounding incredible by the way) going full blast over the chord changes to Doxy. It studio-fades in at the beginning and they’re already shredding. The energy never dips. They swim through variations and tempo changes, fully exploring improvised motifs before breaking back into romping swing. Although they play continuously, the album is broken up into twelve tracks, the titles of which goofily rhyme with the word Doxy. At the end of the album, the audio hard cuts to silence (though it’s clear that the band was still playing in the studio). There’s this funny feeling of “I know they played it for 78 minutes, but it feels like they could have been playing for hours before the fade in and after the hard cut out.” and it really gives a sort of bizarre experience of time, you get half way through and have no idea if you’ve been listening for five minutes or fifty or five hundred.

The album cracks me up, but I also love it for all the reasons I love any other great jazz album: the swing feel, the harmonic interplay, the sound and passion and freedom. That’s the thing about Gravitas Ridiculum. Each project proves that there is no necessary dichotomy between hilarity and intensity, between humor, insanity, absolute seriousness, and deep emotion. Something can dialectically be completely funny, absurd, and earnest. It’s a celebration of the insane world we live in, a fiercely optimistic approach.

In the arts, critics love putting people into categories. There are the minimalists and the abstract expressionists, the cubists and the artificial realists. There’s new complexity, neoclassicism, post- and avant- whatever, and there’s dada. The irony of this paper is that much of the project of the postmodernists was to show that these categorizations can be damaging. The whole point was to let a piece of art be what it is! They claimed that by drawing a box around a body of creative work and saying “these people ascribe to this particular -ism,” you erase nuance, orient yourself towards the past, and bias yourself towards easily categorized work.

But despite those risks, I’ve decided to draw a new line in the sand. Categorizing art gives people context, and gives them the ability to construct a narrative for themselves. Even if that narrative ends up oversimplifying, it can act as a nice starting point, without which audiences or students might be turned off from the subject completely due to its opacity. So I’m presenting the Gravitas Ridiculists in the hopes that the term can be a tool to understand an emerging creative phenomenon. It’s a compositional strategy that I encourage my own readers to try out in their artwork for a fresh creative experience. I believe it will bear a lot of fruit in the years to come.

Begin failed earlier draft:

The video that kicked it off for me was the classic 2015 meme “‘just do it’ motivational speech.” It’s the one where Shia LeBeouf stands in front of a green screen and screams “JUST DO IT” and “don’t let your dreams be dreams,” at a camera for about a minute. It’s a really interesting video because it sits in this strange in-between space: yes it’s hilarious, silly, ironic, and a meme, but if you look past the bizarre facade for a second it becomes apparent that he’s incredibly serious. The video starts with ridiculousness and irony, but then smashes those things up with absolute sincerity, total commitment to the concept, and authentic human emotion.

The video sent me down a Shia LeBeouf YouTube rabbit hole. He seemed pretty unhinged at the time, and was traveling across the country on some weird social media driven art project where he would meet up with fans and travel with them for a while. I checked out some interviews with him and he said he was getting into this concept called “Metamodernism.”

Despite the fact that at the time I had no idea what modernism or postmodernism were (which metamodernism is supposed to be a response to), I started checking out art projects that deemed themselves “metamodernist” and thought “okay I see what they’re going for, I’m into that.” Only over time did I realize the potential for this philosophy/worldview to positively impact our society and solve some serious philosophical problems posed by the two previous -isms.

But what happened to get us here? To understand, let’s take a super simplified look at the progression from modernism to postmodernism to metamodernism.

The modernists are the enlightenment thinkers. They’re the ones who say “we can champion logic and reason to better our lives. Objective truth reigns, and science will lead us to the answers and utopia.” The modernists believe in facts, a single viewpoint of truth (not “true for you, untrue for me”), and believe in the noble cause of seeking that universal objective truth. They see themselves as standing on the shoulders of giants, and they believe in the classical established canon of thinkers in their field.

The postmodernists are the ones who pushed back on the presumptions that the modernists made. They’re the ones who said “Objective truth doesn’t exist! The nature of reality is infinite and unknowable. Your ideas about truth and reality are inescapably biased by your life experience, upbringing, nature, and your language. What you call ‘truth,’ I call a manifestation of your beliefs, worldview, and your personal tastes.” Under postmodernism, all the definitions crumble, certainty becomes impossible, all knowledge is relegated to the realm of “that’s just like, your opinion, man.”

But, what does this stance do for us? Postmodernism, with all its useful corrections about the nature of knowledge, is an exceedingly negative worldview. It tells you (convincingly) why objectivity is a sham, but it doesn’t really give you any advice about what to do with this information. It offers no alternative, no course of action.

So, in comes metamodernism. Metamodernists say to the postmodernists “I hear your issues with objectivity. You’re right! Subjectivity is very important, and we can’t prove some of the things we thought we could. But going around telling people what’s wrong and terrible isn’t helping any more. We’re way past the point of diminishing returns on these questions about ‘What is knowable in this world? What is truth? Is there objective good?’ and providing negative responses to these questions (nothing is knowable, etc.), while epistemologically valid in many ways, doesn’t actually accomplish anything in people’s lives. At least the modernists were striving towards a utopia. You’re not striving for anything! So let’s strive for a utopia again, now having learned about your very legitimate criticisms against the intellectual blindspots of the modernists.”

In short: the modernists look for some grand, sweeping theory about ultimate truth. Postmodernists tell the modernists that ultimate, all-encompassing truth is impossible. Metamodernists tell the postmodernists that they might be right about that, but you should still try!

Now let’s look at these ideas in music:

Modernism is being Charlie Parker or Beethoven. Your music is an achievement, and an outpouring of human intellect and emotion that shatters the ceiling that was previously set. It is the continuation of a tradition; you’re not reinventing the wheel, but you are coming out with a new model that’s faster, more elegant, better designed than those prior. It’s reaching new heights, it’s progress in your field.

Postmodernism is being The Art Ensemble of Chicago or György Ligeti. It’s pushing the boundaries of music in a different way. It’s saying “We’re questioning your very notion of what music even is! We’re questioning your notion of what music can be.” In other words, if Charlie Parker is pushing the boundaries upwards, then the Art Ensemble of Chicago is pushing the boundaries outwards.

Postmodern musicians are the ones saying “There is no such thing as right or wrong in art. Your ‘Music Theory’ is just an arbitrary set of stylistic descriptors that, when followed, lead you back to your own 19th century European Aristocratic approach to music. That doesn’t make it ‘correct’, that makes it like a recipe book that can be used to cook one specific type of cuisine. You can’t use your own criteria, your own recipes, as the ruler to measure other people’s art. It’s apples to oranges, and you don’t get to tell me that your apple is the highest achievement of all fruit.”

It’s important to note that musicians (and more broadly, artists) didn’t just speak out about these questions of objectivity in their conversations and interviews, they actually railed against the modernist establishment through the content of their art. When Marcel Duchamp comes along and puts a urinal in the Museum of Modern Art, it’s an artistic act, but it’s also one that’s intended to blast away your held definition of art and force you reevaluate it. Art that’s made specifically to challenge modernist preconceptions employs a technique called auto-critique, and at this point it’s a well established tradition in itself. Avant-gardeists have been coming along for decades and breaking all the “rules” of art, just to prove that those weren’t rules after all.

There was certainly a time and place for this attitude, when the establishment was married to its ideas about objective beauty and “greatness,”

But now that postmodernism has more or less ripened, musicians are left balancing on a tricky tightrope. On the one hand, musicians who are still going around saying “There are no rules!! Look at my whacky dissonant piece that only exists to demonstrate that there are no rules, and look how clever I am for writing it!” receive warranted eye-rolls from basically everyone. There is no establishment to rail against anymore. They’re proving a point that’s already well proven, and re-proving it is getting to be annoying. We get it! There are no rules. You’re right. I don’t need you to show me anymore.

And for huge swaths of the population of artists and listeners, the stylistic markers that define postmodernism (dissonance, a conceptual nature, etc.) do nothing for them emotionally, they just don’t care about those sounds.

On the other hand, if you don’t engage with postmodernism at all, then you risk seeming like you’re oblivious to the artistic possibilities that have been opened up since the postmodernists came along. You risk being criticized for being a follower, a sheep who hasn’t considered the greater context of how their art fits in society. At least for me, it doesn’t matter how great your Art Blakey tribute album sounds, I’m always going to listen to an Art Blakey album instead.