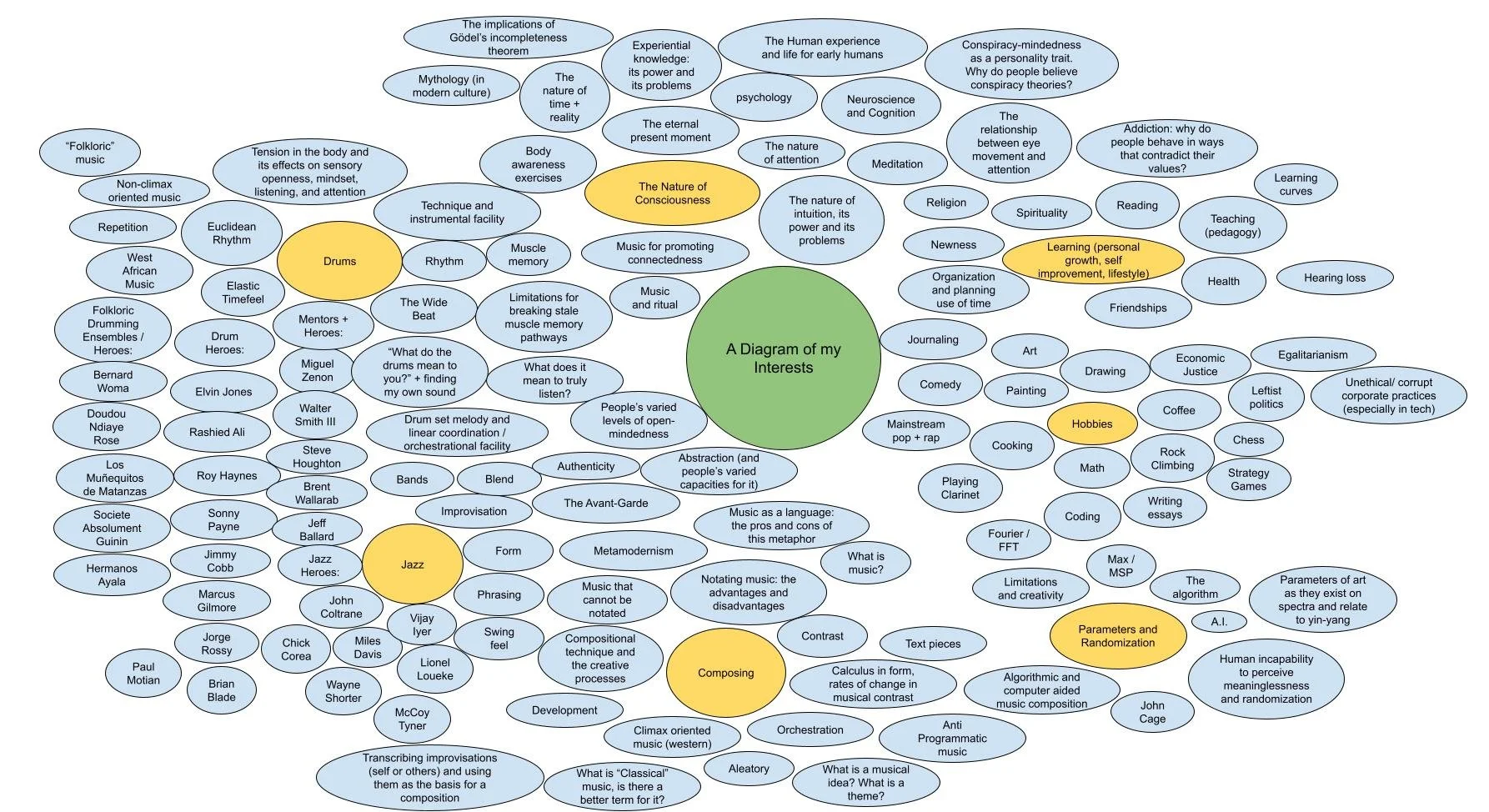

A Diagram of my Interests

Supplement to a Diagram of my Interests

or

Hierarchical vs Territorial Thinking

Thinking hierarchically can be a poison in the arts, yet it heavily pervades both the jazz and contemporary classical worlds. If your only goal in life is to be the greatest drummer, the greatest saxophonist, or the greatest composer alive, then you’ll make yourself miserable by defining your own self worth against the accomplishments of others. You’ll grow to resent incredible art. Instead of taking in the beauty of a masterpiece with humility and awe, you’ll feel squashed by its quality, fearing it’s something you’ll never live up to. Music of your own creation will be nothing more than bizarre peacocking intended to prove your skill. You may even find yourself putting down the music of others in a (probably subconscious) attempt to make yourself feel like you’re higher up on the ladder. Or, you may become a gatekeeper to your particular sub-genre in an attempt to keep too many newcomers from crowding your artistic world and stealing your imaginary deserved spot near the top of the hierarchy you’ve created in your head.

Steven Pressfield outlines the dangers of a hierarchical mindset in his book The War of Art. He shows that perceiving art as one great pecking order both undermines the quality of your work and erodes your emotional wellbeing. He also offers an alternative: a territorial mindset.

With a territorial mindset, you get to see your artistry as a unique intersection of interests, life experience, and personal aesthetic values. When others ask “who’s the better drummer, you or [blank]?” or “who’s the better composer?” You get to shrug those questions off: It’s apples to oranges. You have your sound, and other people have theirs. You study and practice the things that resonate with your tastes, interests, and values, because those things are the signposts on the path to authentic self expression through art. When you hone your technique, craft, and virtuosity, you don’t do it for the sake of advancing your rank in some meaningless imaginary list of “greatest [blank]s,” but rather because you find great joy in the creative process and making the best music you can.

This is the mindset that I bring to my PhD and DMA applications. If I’m admitted to any of these programs, it won’t be because I’m the greatest in the world at any single skill, but rather because I’ve cultivated a unique combination of skills that align with my personality and creative values.

This is not to mention that following each interest down the rabbit hole has only served to strengthen the other areas of my creative life. The only thing that makes my drumming anything close to unique is the fact that it’s informed by a wide breadth of influences. The same idea holds true for my compositions, essays, and visual art: Their strength comes from the diversity and authenticity of my creative territory. They say there’s nothing new under the sun. Any innovation in my work comes only from the fact that nobody else has combined the exact same set of (already existing, sometimes very old) ideas in the exact same way I have. My territory is unique and my own. Everybody’s is!

And at the risk of being too political, my applications are coming at the same time as a major fork in the road for many institutions of higher learning. The internet and increased globalization have brought us to a societal reckoning point: It can now no longer be ignored that blindly championing European cultural practices as being the most “civilized,” “highly advanced,” or generally “the greatest” is a deeply problematic worldview that is perhaps even more deeply ingrained into the fabric of Western culture and music education.

The question is: Will universities double down on a hierarchical mindset with regards to classical music of the 18th and 19th centuries, placing it at the top as “the greatest, most highly advanced, most sophisticated” form of music that exists? Or will they finally adopt a territorial approach that states that classical music occupies a unique place in history (and the present) as the product of a fascinating cocktail of social factors, but at its heart is inherently no better or worse than any other musical culture? Will they recognize that classical music rests on the same bedrock of the universal human urge to create song that all music rests on? That the societal values and the tools at hand used to sculpt this urge into sound are the only things that differ across time and place?

I made this diagram of my interests for a few reasons. The first is the same reason I started my blog: I hope that by documenting and carefully examining which topics I’m most excited about I can explore them more deeply and eventually find some kind of closure with them. I’m hoping to upgrade many of these ideas from vague interests to areas of scholarly expertise and/or instrumental mastery.

The second reason is that I’m trying to find a succinct way to package up my artistic life and present it to potential Doctoral programs. I felt that even if this diagram doesn’t make it across their desk as an end product, it would still be useful to make as preliminary application work, something to refer to as I organize my portfolio.

The third reason is that it’s a really interesting creative resource. If we follow this “nothing new under the sun, all new ideas are new combinations of existing ideas,” notion further, then uncharted creative territory is as easy to discover as closing your eyes and pointing your finger at 2-5 random points on the screen. A series of paintings inspired by the swing feel of some of my drum heroes? A text-based composition that utilizes randomization to make choices about orchestration? Transcribing a Rashied Ali solo, using the transcribed material as the basis for a new orchestral work, and incorporating guided meditation into the piece at specific moments to explore the nature of attention and relaxation in music? Not every combination of ideas is going to be a slam dunk, but at least many of them legitimately have not been done before, and there’s something to be said for that.

I tried to structure the diagram in such a way that close proximity between circles indicates that they’re more closely related in my mind than two circles that are far apart (though this was not possible in every case). The gold circles are broad areas of interest and the blue ones are sort of sub categories. For the musical heroes, I tried to keep the list very short and only include a person if they’ve had an enormous impact on my musical development and beliefs. It’s an especially goofy list of jazz heroes: besides the fact that it’s painfully incomplete, I’ve realized that many of the musicians who I care about the most in the jazz tradition are the ones you learn about during your first week of jazz camp (Miles, Coltrane, Chick). The others are ones who have innovated in bringing an element of folkloric rhythm into their jazz practice (Vijay, Lionel Loueke, Miguel Zenon) in a way that I hope to emulate.

The diagram is far from complete, and many of the ideas are either too specific or too broad to give any real information about my music (“wow, I guess he’s interested in ‘rhythm’ with regards to the drums!”). Like my Euclidean Rhythm post, I’m going to try to update this and edit it further after I’ve already posted it as I think more about things I could include or clarify. Nonetheless, making it was a fun and enlightening exercise in introspection, and it gives me new ideas about how to connect these interests in the future.

If you’ve made it this far in the blog, I appreciate you as always, and I have two challenges/requests for you: one is to create a similar diagram of your own interests and show it to me, and the other is to send me some reading or listening material that relates to my interests. I’m always trying to go deeper into these topics, which is one of the reasons I’m interested in getting a doctorate in the first place, and any new avenue for exploration would be greatly appreciated.